Astelin

Purchase genuine astelin on-line

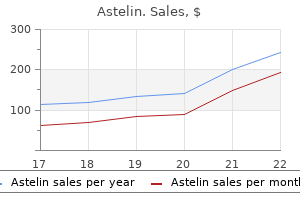

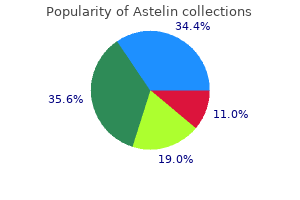

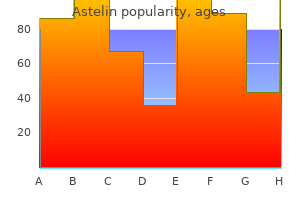

Cardiovascular risk factors in hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: role in development of subsequent cardiovascular disease allergy partners purchase astelin 10ml. Long-term follow-up of pediatric patients receiving total body irradiation before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and post-transplant survival of >2 years. Early and progressive insulin resistance in young, non-obese cancer survivors treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Relapse after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for refractory anemia is increased by shielding lungs and liver during total body irradiation. Lethal pulmonary complications significantly correlate with individually assessed mean lung dose in patients with hematologic malignancies treated with total body irradiation. Pulmonary function following total body irradiation (with or without lung shielding) and allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplant. Feasibility study of helical tomotherapy for total body or total marrow irradiation. Image-guided total-marrow irradiation using helical tomotherapy in patients with multiple myeloma and acute leukemia undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Total body irradiation with volumetric modulated arc therapy: Dosimetric data and first clinical experience. The effective date is the first of the first month after 60 days of the date the approval was finalized. Many standpoint, acute leukemia occurs in 30% factors can inhibit the induction of remission. Identification of corresponding factors is important to increase the likelihood of successful inductions. Standard and high-risk groups are widely known Objective To assess for associations between hematological to have different outcomes, therapy, and even parameters and induction of remission in children with acute prognoses. Kariadi Hospital from May of the induction phase, consolidation, re-induction, 2014 May 2016. The main induction phase achievement in independent variable was induction of remission. Hematologic parameters consisted 10 years and the high risk group was aged younger of initial of hemoglobin, leucocyte, and platelet than 1 year or older than 10 years. Initial hemoglobin level was Data were collected from subjects medical categorized anemic and non-anemic according to records. The other parameter was initial platelet count analysis and relative risk; logistic regression test was which categorized into normal (150,000-400,000/ used for multivariate analysis. The outcomes the Research Ethics Committee of the Diponegoro of induction was remission and no remission. Remission was defined with the blast cell in bone marrow puncture 20%, while no remission was if the blast cell? Baseline characteristics are shown in of mediastinal mass, or blast cell absolute count in Table 1. Bivariate analysis factors associated with induction Subjects mean hemoglobin level was 8. In a Korean study, the the median Variables Remission No remission P value hemoglobin level was a similar 8. Patients with neutropenia are susceptible in the induction phase to be approximately 80%. Low platelet counts after induction therapy for childhood acute lyphoblastic leukemia are strongly References associated with poor early response to treatment as measured 1. In: Permono B, by minimal residual disease and are prognostic for treatment Sutaryo, Urgasena I, Windiastuti E, Abdulsalam M, editors. O?Connor D, Bate J, Wade R, Clack R, Dhir S, Hough R, Influencing and Treatment Outcome. Due to high unmet patient needs, multiple forms of novel therapy are currently in clinical trials. A disease overview is transformative technology, unparalleled data and included in Figure 2. Incidence is slightly more frequent in male 11,12 followed by consolidation or intensifcation treatment. This is based on the patients who are 50 years or younger have consistently higher prevalence of unfavorable cytogenetics and been in the range of 60% to 70% in most large cooperative antecedent myelodysplasia, along with a higher group trials of infusional cytarabine and anthracycline. Patients who received midostaurin with standard from a matched sibling or an alternative donor, which induction and consolidation therapy experienced constitutes the best option for long-term disease control. Patients can re-attempt induction chemotherapy regiments or go into a clinical trial. These studies have generally demonstrated safety for treatment resistant 17p-deleted chronic lymphocytic and immune correlates but no clinical efcacy. Attempts to consolidate molecular and clinical information into a single prognostic Molecular biomarkers are used to predict patient index have been pursued but not implemented. Well-known chromosomal sequencing, have been used to identify novel risk profles35 abnormalities may be identifed in approximately 50% that may be more feasible and accurate. Knowledge of sites and investigators heterogeneity of this indication and the current increase conducting prognostic and targeted molecular or in the number of oncology clinical trials. Figure 5 provides a comparison of the conventional, Key clinical trial benchmarks (per Citeline experience-driven approach vs. In contrast, not appear to vary by patient population the evidence-driven approach uses a data-driven site selection strategy that leverages multiple healthcare. Duration of enrollment is higher in the data sources to identify the target patient population ?untreated population (43 months) vs. This is done contacted to make referrals for the surrounding through a multi-step approach: investigator sites. Identify high potential sites based on patient potential enrollment to meet the study objectives. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Prognostic signifcance of the European LeukemiaNet standardized system for reporting cytogenetic and molecular alterations in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Acute leukemia incidence and patient survival among children and adults in the United States, 2001-2007. Prevalence and incidence of acute myeloid leukemia may be higher than currently accepted estimates among the? The fate of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia who fail primary induction therapy. Defning and treating older adults with Acute Myeloid Leukemia who are ineligible for intensive therapies. Current approaches in the treatment of relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Combined molecular and clinical prognostic index for relapse and survival in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Mutational spectrum and risk stratifcation of intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia patients based on next-generation sequencing. Ekaterina Vorozheikina has 15 years experience In his current role as Strategic Alliance Lead, he in clinical hematology. His ultimate goals are to accelerate hematological disorders, including diferent types customer growth and to ensure strong business results of lymphomas, acute leukemias, chronic myeloid by driving a consistently positive customer experience in malignancies, etc. Maria Ignacia Berraondo is a physician trained and board certifed in hematology based in Buenos He brings more than 20 years of experience in Aires, Argentina. She pursued her medical degree at El biological research in academia, biotechnology and Salvador University, in Argentina. She completed her clinical services including fve years of experience in medical hematology training in a teaching hospital, planning and design of clinical development plans and Hospital Alvarez of Buenos Aires and is certifed as a protocols for drug development. She has been working as clinical hematologist for the last 10 years and received a special training in bleeding disorders in Favaloro Foundation. In this role she leverages global real-world healthcare data to facilitate oncology clinical trial development. The focus of her research as a post-doctoral fellow at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was on kinomeic reprogramming and the identifcation of novel drug targets for the treatment of solid tumors. She brings more than six years of oncology drug target identifcation and development experience. This guide is not intended to be used as a stand-alone document and should be used in conjunction with the full manuscript published in the April 2011 issue of Arthritis Care and Research. Details of the development of are intended to provide guidance the recommendations can be found in the full manuscript.

Generic astelin 10ml online

Solid tumors are frequ ding of late effects in young adult survivors of childho enty seen after a latent period of 8-25 years allergy medicine vegan buy discount astelin 10ml on-line. The health status of ught that acquired hereditary abnormalities incre adult survivors of cancer childhood. Eur J Cancer 34: ase the secondary cancer risk but in a study, no dif 694-698, 1998. Turkish Jour Late side effects of cancer are increasingly seen due nal of Cancer 22: 13-19, 2007. Thus, we can detect the complications of cer Survivors Treated on Southwest Oncology Group cancer treatment earlier, prevent sequelae with Protocol s8897. Multi-com ponent behavioral intervention to promote health pro tective behaviors in childhood cancer survivors: the protect study. J Clin sociated cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood can Oncol 20: 1215-1221, 2002. Semin Oncol 30: xicity from intensive chemotherapy combined with ra 730-739, 2003. Relative risk vourable and unfavourable effects on long-term survi of stroke in head and neck carcinoma patients treated val of radiotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview with external cervical irradiation. Antican enalapril therapy for left ventricular dysfunction in do cer Res 17: 4739-4742, 1997. Left ventricular and and warfarin for the treatment of limited-disease small cardiac autonomic function in survivors of testicular cell lung cancer: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B pi cancer. Reversibility lung from cancer therapy: Clinical syndromes, measu of trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity: New insights rable endpoints, and potential scoring systems. Int J based on clinical course and response to medical tre Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31: 1187-1203, 1995. Assessment pulmonary toxicity syndrome following high-dose che of cardiac dysfunction in a randomized trial comparing motherapy and bone marrow transplantation for bre doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by pacli ast cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157: 565-573, taxel, with or without trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy 1998. Infertility and premature menapouse in child ne disorders following treatment of childhood brain tu hood cancer survivors. Magnetic mone secretion and response to growth hormone the resonance imaging in the evoluation of treatment rapy after treatment for brain tumour. Growth hor dal ideation and attempts in adult survivors of child mone status in adults treated for acute lymphoblastic hood cancer. Pediatr Blood Growth hormone treatment of children with brain tu Cancer 51: 724-731, 2008. Journal of Clini renal function in patients with irradiated bilateral Wilms cal Endocrinology and Metabolism 85: 3227-3232, tumor. J Clin En evaluation of survivors of acute lymphoblastic docrinol Metab 81: 3051-3055, 1996. Osteonec lity after extended retroperitoneal lymph node dissec rosis as a complication of treating acute lymphoblastic tion for testicular cancer. Bispho sphonate (zoledronic acid) associated adverse events: single center experience. Second neoplasms in survivors of childhood cancer: findings from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Bilateral breast cancer in a survivor of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a case report. Acute myeloid leukemia in children treated with epidophyl lotoxins for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The BioTrust is a program that oversees the storage and research use of blood spots that are left over after newborn screening. Wisconsin has developed a method for analyzing 8 steroids in dried blood spot specimens. The goal is to develop a comprehensive data model for newborn screening programs to use to guide disease identification. We do not expect to find any changes for infants born to non Hispanic white mothers. The primary source of exposure to these pesticides is through diet, mainly through dairy products and fish, and the fetus can be exposed through the placenta. As such, these dried blood spots may enable the investigation of angiogenic markers and their relevance to childhood health outcomes that are not identified until later in life (such as autism spectrum disorder). The work here seeks to demonstrate the feasibility and potential utility of measuring a panel of markers in neonatal dried blood spots. The proposed panel is cost effective and uses a minimal amount of dried blood spot. We will conduct a variety of statistical, qualitative and mixed methods analyses using both quantitative and qualitative data to determine answers to the aims of our study. We will also consider the timing of pregnancy in our analyses, as the prenatal data are collected at three distinct time points. Available research is limited in the extent to which it examines the role of babies fathers in the lives of pregnant women. As we have reported, the few studies that have explored paternal effects on birth outcomes have generally excluded understanding the dynamic, complex, and often correlated maternal-paternal relationship. The proposed study will assess whether and how fathers may have an impact on successful birth outcomes (birth weight, gestational age). Our study of Black fathers and birth outcomes builds on our previous studies and those of others although differing in several important ways. Innovative aspects of this study include direct collection of data from fathers, assessment of the mother-father relationship, and inclusion of measures rarely studied, particularly as related to fathers, such as discrimination, neighborhood environment, and telomere length across the life course. Both fathers and mothers will be interviewed during the prenatal period and within the first week after birth. Thus, multiple sources of data will be available to provide a more comprehensive assessment of fathers as part of the social environment in which Black women experience pregnancies. We aim to: (1) Determine how the mother-father relationship (support, conflict) during pregnancy relates to maternal and/or paternal factors; and (2) Determine whether and how paternal factors relate to birth outcomes (birth weight, gestational age at birth). Understanding mechanisms through which these processes unfold is imperative for articulating risk and protective factors influencing birth outcomes. Although the literature has identified a number of risk factors associated with mothers, little attention has been given to understanding the role of fathers related to birth outcomes. Understanding their contributions to birth outcomes could expand service, intervention, and policy efforts beyond mothers. This could help improve current laboratory tests used to detect disorders through newborn screening (Genetic Studies of Diabetes Mellitus) Newborn Screening for Earlier Diagnosis and Treatment of Congenital Diabetes Institution/Agency: University of Chicago Year Approved: 2018 Samples Requested: 11,500, Additional study specific consent obtained Year Released: No samples released to date Study Summary: Congenital diabetes is a rare but treatable form of diabetes diagnosed during the first days or months of life. Symptoms are often difficult to recognize in infants, causing a delay in diagnosis and possible adverse health outcomes; identifying congenital diabetes earlier could reduce morbidity and encourage proper treatments. Patients with these mutations normally have significant hyperglycemia within 24-72 hours of life, making it possible to be detected on dried blood spot samples. Identifying hyperglycemia through newborn screening also prompts the implementation of sulfonylurea drugs instead of insulin as an initial treatment measure. Detecting congenital diabetes early through newborn screening could be an efficacious public health initiative. The goal of this study is to support the inclusion of congenital diabetes into newborn screening programs by demonstrating the feasibility to screen for congenital diabetes, highlighting the importance of preventing congenital diabetes morbidity by including it in newborn screening, and providing evidence on appropriate treatment directed toward improving long term neurodevelopmental outcomes. Common symptoms include hypotonia (95%), oculogyric crisis (86%), and developmental delay (63%). Other frequently described symptom are temperature instability, movement disorders, feeding or speech difficulty, insomnia, and irritability. Many patients die before age 10 due to complications of seizures or feeding and breathing difficulties. Prior to treatment, the patients were bedridden, lacked head control or the ability to speak, and experienced frequent oculogyric crisis. After therapy (follow up, 15-24 months), the patients gained weight, had improved motor and cognitive function, fewer oculogyric crises, and increased emotional stability.

Diseases

- Warburton Anyane Yeboa syndrome

- Phenol sulfotransferase deficiency

- Alopecia macular degeneration growth retardation

- Verloove Vanhorick Brubakk syndrome

- Erythema nodosum

- Dyserythropoietic anemia, congenital type 1

Generic 10ml astelin with mastercard

More details on each individual study can be found in the evidence tables (see Appendix I) allergy medicine 19 month old discount astelin 10 ml online. Infants in this group are likely to require very careful nutritional support that often requires a combination of enteral and parenteral feeding in the early stages of their postnatal care followed by a gradual normalisation of feeding with greater maturity. It is assumed that the frequent regurgitation and physiological reflux described in many post-term infants will be a very common problem in this population. This can be further complicated in some premature infants with additional difficulties that may put them at greater risk of emesis following other complications of prematurity, such as nectrotizing enterocolitis. This study examined the association between prematurity and esophagitis at different ages. The studies reported different outcomes including esophagitis in 1 study (Forssell et al. The settings of the studies included a paediatric surgical centre, medical centre and hospital. Confirmation of the diagnosis was based on the explicit diagnosis of esophagitis, combined with the described macroscopic findings at endoscopy that were found in the charts. Reflux was considered pathologic if the proportion of total time with pH<4 during a 24 hour period exceeded 4%. One study reported a statistically significant association between prematurity (gestational age of 33 to 36 weeks) and the risk of developing esophagitis (two age groups analysed: 9 years or less and 10 to 19 years). This study also reported a statistically significant association between extreme prematurity (gestational age of 32 weeks or less) and esophagitis at 9 years or less and at 10 to 19 years. The conditions that were targeted by the guideline development group were hiatus hernia (where there is a telescoping effect or invagination of the stomach back through the gastro-oesophageal junction), diaphragmatic hernia (where there is an abnormal weakness or discontinuity in the tissue plane between the thorax and abdomen which can result in the herniation of part of the gastro-intestinal tract into the thoracic space) and finally, oesophageal atresia (where there is a congenital abnormality in the development of the oesophagus with or without the trachea that invariably requires a complex surgical repair in infancy and may be linked with other complex congenital abnormalities in a variety of associations). The age of the subjects varied from infants with a mean age of 28 months in 1 study (Steward et al. The studies reported different outcomes including erosive esophagitis in 1 study (Steward et al. The settings of the studies included a spastic centre, hospitals and primary care. Each patient was examined fluoroscopically, after the ingestion of 4 to 6 ozs of barium, in the supine position and then prone to see whether a hernia or reflux became visible. Non specific symptoms such as epigastric pain to identify cases was not used unless they were recorded alongside reflux symptoms. Patterns of potential inheritance or increased probability of recurrence have been recognised in many conditions in advance of more detailed genetic explanations. This study was undertaken in Northern Ireland and included 1133 adolescents (and their parents) selected from post-primary schools. This study reported on family history of epigastric pain, heartburn and acid regurgitation. Outcomes included epigastric pain, heartburn and acid regurgitation in the adolescent defined in various ways. This study found that a history of epigastric pain in either or both parents is not significant in predicting the odds of epigastric pain in the adolescent. This study found that a history of heartburn in either parent is not statistically significant in predicting the risk of heartburn in the adolescent, but a history of heartburn in both parents is associated with the odds of heartburn in the adolescents. This study found that a history of acid regurgitation in either or both parents is statistically significant in predicting the odds of acid regurgitation in the adolescent. The exact mechanism may vary and could include increased intra-abdominal pressure, lower oesophageal sphincter dysfunction or poor diet. The definition of different levels of obesity in children is dependent on the interpretation of the Body Mass Index with reference to age appropriate centile charts for boys and girls. Sample sizes for the analysis of this risk factor were reported in 3 studies and ranged from 153 to 9900. The age of the subjects varied: they were 7 to 16 years in 2 studies (Stordal et al. The severity and frequency of symptoms were classified into different grades based on a scale used in previous studies. The questionnaire consists of a history of any sickness in the last 2 weeks and 5 symptoms experienced over the last week (vomiting, nausea, heartburn, regurgitation and dysphagia). A score was given for each symptom and a validated total score of 3 or more was considered a positive reflux symptom score. A second study did not find a statistically significant association between being overweight and the risk of developing epigastric pain, heartburn or acid regurgitation. One study reported a statistically significant association between obesity and a positive reflux symptom score. The other study which looked at the association between obesity and epigastric pain, heartburn or acid regurgitation found a statistically significant association between obesity and acid regurgitation but not between obesity and epigastric pain or heartburn. The study found a statistically significant association at 6 to 11 years and at 12 to 19 years, but not at 2 to 5 years. The guideline development group focused its attention on the quality of studies and level of imprecision reported in the results. It was noted that the available evidence was limited in quantity and quality and therefore the group relied on their clinical experience when making recommendations. Only 3 studies were identified that measured this risk factor, and of these, only 1 presented adjusted odds ratios. The group recognise that the literature is hampered by vague generalisations and a failure to look at specific diagnoses in assessing the problem. Similarly, children with these problems are often suffering a variety of problems that may be contributing to complex feeding problems, chest disease, pain, faltering growth and emesis. The third study did report adjusted odd ratios and concluded prematurity was a risk factor for subsequent developing esophagitis. The group focused on this study as it reported an unambiguous complication of reflux and used robust methods to analyse the data. However, the guideline development group was unsure if this conclusion should apply to infants during the initial phase of prematurity. No studies were identified that could be assessed according to the chosen criteria and methodology on the premature infants while they were still premature (and being cared for on the neonatal unit). The evidence described above was based on children and young people who had been born prematurely and went on later to develop symptoms. The group discussed their experience, which suggested that there were higher rates of overt reflux in premature infants for the reasons outlined in the section introduction; that is, it was proposed that higher rates of reflux are likely to be caused by the relative immaturity of gastrointestinal system in this group together with other factors. The group debated whether the higher rates of reflux observed was normal physiology or abnormal (pathology) and whether it would require treatment or if treatment offered to older infants was potentially harmful. No conclusion could be reached and no recommendation was made on the management of reflux in premature infants. Similarly, it was agreed that detailed suggestions in terms of complex feeding regimes for hospital neonatal units was beyond the scope of this guideline. The study was prospective and provided adjusted odds ratios, and was graded as moderate to high quality evidence. The group thought it was unlikely that a simple genetic component could explain all the outcomes. Therefore, it was unknown what effect family history would have on younger children and infants. However, it was agreed by the group that lifestyle factors would take a considerable time to manifest themselves, so it would be older children and young adults where this finding would be most relevant. The group believed that excess weight was an issue that developed with age; therefore the results of this study were appropriate for the population of interest. However, the group agreed that healthy eating, regular exercise and, where necessary, safe weight loss programmes are likely to be beneficial for all obese children and adults as they may reduce a number of potentially serious co-morbidities. The decision to give a trial of acid suppression therapy should be influenced by the presence of a significant neurodisability as specified in Recommendation 30. Endoscopy is usually performed under sedation or more frequently under general anaethesia in children, and there are small but associated risks. Oesophageal pH monitoring can be a somewhat distressing investigation, requiring placement of a naso-oesophogeal probe. Conversely, false negative clinical evaluation could result in delayed investigation or treatment. Therefore, initial diagnosis has to be based on risk factors, symptoms and signs, and examination.

Cheap 10ml astelin overnight delivery

Research suggests that testosterone allergy treatment wiki order astelin 10 ml mastercard, oxytocin, and vasopressin are also implicated in female sexual motivation in similar ways as they are in males, but more research is needed to understand these relationships. Sexual Responsiveness Peak: Men and women tend to reach their peak of sexual responsiveness at different ages. For men, sexual responsiveness tends to peak in the late teens and early twenties. Sexual arousal can easily occur in response to physical stimulation or fantasizing. Sexual responsiveness begins a slow decline in the late twenties and into the thirties, 260 although a man may continue to be sexually active. Through time, a man may require more intense stimulation in order to become aroused. Women often find that they become more sexually responsive throughout their 20s and 30s and may peak in the late 30s or early 40s. This is likely due to greater self-confidence and reduced inhibitions about sexuality. Proper use of safe-sex supplies (such as male condoms, female condoms, gloves, or dental dams) reduces contact and risk and can be effective in limiting exposure; however, some disease transmission may occur even with these barriers. Historically, religion has been the greatest influence on sexual behavior in the United States; however, in more recent years, peers and the media have emerged as two of the strongest influences, particularly among American teens (Potard, Courtois, & Rusch, 2008). Mass media in the form of television, magazines, movies, and music continues to shape what is deemed appropriate or normal sexuality, targeting everything from body image to products meant to enhance sex appeal. Cultural Differences: In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting 261 partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties, when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield & Rapson, 2006). It is a personal quality that inclines people to feel romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of a given sex or gender. Sexual orientation is independent of gender; for example, a transgender person may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, polysexual, asexual, or any other kind of sexuality, just like a cisgender person. Research done over several decades has supported this idea that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex/gender to exclusive attraction to the same sex/gender (Carroll, 2016). Bisexuality was a term traditionally used to refer to attraction to individuals of either male or female sex, but it has recently been used in nonbinary models of sex and gender. Alternative terms such as pansexuality and polysexuality have also been developed, referring to attraction to all sexes/genders and attraction to multiple sexes/genders, respectively (Carroll, 2016). Being asexual is not due to any physical 262 problems, and the lack of interest in sex does not cause the individual any distress. Development of Sexual Orientation: According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence. However, this is not always the case, and some do not become aware of their sexual orientation until much later in life. It is not necessary to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Some researchers argue that sexual orientation is not static and inborn but is instead fluid and changeable throughout the lifespan. There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a particular sexual orientation. However, biological explanations, that include genetics, birth order, and hormones will be explored further as many scientists support biological processes occurring during the embryonic and and early postnatal life as playing the main role in sexual orientation (Balthazart, 2018). Bailey and Pillard (1991) studied pairs of male twins and found that the concordance rate for identical twins was 52%, while the rate for fraternal twins was only 22%. Bailey, Pillard, Neale, and Agyei (1993) studied female twins and found a similar difference with a concordance rate of 48% for identical twins and 16% for fraternal twins. Schwartz, Kim, Kolundzija, Rieger, & Sanders (2010) found that gay men had more gay male relatives than straight Source men, and sisters of gay men were more likely to be lesbians than sisters of straight men. Fraternal Birth Order: the fraternal birth order effect indicates that the probability of a boy identifying as gay increases for each older brother born to the same mother (Balthazart, 2018; Blanchard, 2001). A meta-analysis indicated that the fraternal birth order effect explains the sexual orientation of between 15% and 29% of gay men. Hormones: Excess or deficient exposure to hormones during prenatal development has also been theorized as an explanation for sexual orientation. In 263 contrast, too little exposure to prenatal androgens may affect male sexual orientation by not masculinizing the male brain (Carlson, 2011). Sexual Orientation Discrimination: the United States is heteronormative, meaning that society supports heterosexuality as the norm. Consider, for example, that homosexuals are often asked, "When did you know you were gay? Living in a culture that privileges heterosexuality has a significant impact on the ways in which non-heterosexual people are able to develop and express their sexuality. It can be expressed as antipathy, contempt, prejudice, aversion, or hatred; it may be based on irrational fear and is sometimes related to religious beliefs (Carroll, 2016). Homophobia is observable in critical and hostile behavior, such as discrimination and violence on the basis of sexual orientations that are non heterosexual. Sexual minorities regularly experience stigma, harassment, discrimination, and violence based on their sexual orientation (Carroll, 2016). Research has shown that gay, lesbian, and bisexual teenagers are at a higher risk of depression and suicide due to exclusion from social groups, rejection from peers and family, and negative media portrayals of homosexuals (Bauermeister et al. Discrimination can occur in the workplace, in housing, at schools, and in numerous public settings. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have only come into effect in the United States in the last few years. This demographic limits our understanding of more 264 marginalized sub-populations that are also affected by racism, classism, and other forms of oppression. The hallmark of this type of thinking is the ability to think abstractly or to consider possibilities and ideas about circumstances never directly experienced. If you compare a 15 year-old with someone in their late 30s, you would probably find that the latter considers not only what is possible, but also what is likely. The adult has gained experience and understands why possibilities do not always become realities. They learn to base decisions on what is realistic and practical, not idealistic, and can make adaptive choices. This advanced type of thinking is referred to as Postformal Thought (Sinnott, 1998). Dialectical Thought: In addition to moving toward more practical considerations, thinking in early adulthood may also become more flexible and balanced. Abstract ideas that the adolescent believes in firmly may become standards by which the adult evaluates reality. Adolescents tend to think in dichotomies; ideas are true or false; good or bad; and there is no middle ground. However, with experience, the adult comes to recognize that there is some right and some wrong in each position, some good or some bad in a policy or approach, some truth and some falsity in a particular idea. This ability to bring together salient aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions is referred to as dialectical thought and is considered one of the most advanced aspects of postformal thinking (Basseches, 1984). Such thinking is more realistic because very few positions, ideas, situations, or people are completely right or wrong. So, for example, parents who were considered angels or devils by the adolescent eventually become just people with strengths and weaknesses, endearing qualities, and faults to the adult.

Order astelin

Indications for Prophylaxis Systemic prophylaxis is indicated when the probability of postoperative infection is moderate or high allergy symptoms nausea buy astelin discount, the morbidity of infection is expected to be substantial (including infection of surgically placed prosthetic material), and the benefts of preventing wound infection outweigh potential risks from adverse drug reactions or emergence of resistant organisms. The latter poses a potential risk not only to the recipient but also to other hospitalized patients in whom a health care-associated infection caused by resistant organisms can develop. Major determinants of postoperative surgical site infection include number of microorganisms in the wound during the procedure, virulence of the microorganisms, presence of foreign material in the wound, and host risk factors. The classifcation of surgical procedures is based on an estimation of bacterial con tamination and, thus, risk of subsequent infection. The 4 classes are: (1) clean wounds; (2) clean contaminated wounds; (3) contaminated wounds; and (4) dirty and infected 1 Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery. A patient risk index, which incorporates the American Society of Anesthesiologists preoperative physical status assessment score and the duration of the operation, in addition to the aforementioned wound classifcation, has been demonstrated to be a good predictor of postoperative surgical site infection. The operative procedures are elective, and wounds are closed primarily and, if necessary, drained with closed drainage. Operative incisional wounds that follow nonpenetrating (blunt) abdominal trauma should be included in this category, provided that the surgical procedure does not entail entry into the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts. The benefts of systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis do not justify the potential risks associated with antimicrobial use in most clean wound procedures, because the risk of infection is low (1%?2%). Some excep tions exist in which either the risks or consequences of infection are high. Examples are implantation of intravascular prosthetic material (eg, insertion of a prosthetic heart valve) or a prosthetic joint, open-heart surgery for repair of structural defects, body cavity explo ration in neonates, and most neurosurgical operations. Operations involving the gastrointestinal tract, the biliary tract, appendix, vagina, or oropharynx and urgent or emergency surgery in an otherwise clean procedure are included in this category, provided that no evidence of infection is encountered and no major break in aseptic technique occurs. Prophylaxis is limited to procedures in which a substantial amount of wound contamination is expected. On the basis of data from adults, procedures for which prophylaxis is indicated for pediatric patients include the following: (1) all gastrointestinal tract procedures in which there is obstruction, when the patient is receiving H receptor 2 antagonists or proton pump blockers, or when the patient has a permanent foreign body; (2) selected biliary tract operations (eg, when there is obstruction from common bile duct stones); and (3) urinary tract surgery or instrumentation in the presence of bacteriuria or obstructive uropathy. In contaminated wound procedures, antimicrobial prophylaxis is appropriate for some patients with acute nonpu rulent infammation isolated to and contained within an infamed viscus (such as acute nonperforated appendicitis or cholecystitis). For wounds in which contaminating bacteria have had an opportunity to establish infammation and ongoing infection, antimicrobial therapy should be considered treatment rather than prophylaxis. This defnition suggests that the organisms causing postoperative infection were present in the operative feld before surgery. In dirty and infected wound procedures, such as proce dures for a perforated abdominal viscus (eg, ruptured appendix), a compound fracture, a laceration attributable to an animal or human bite, or major break in sterile technique, antimicrobial agents are given as treatment rather than prophylaxis. Timing of Administration of Prophylactic Antimicrobial Agents Effective prophylaxis occurs only when adequate drug concentrations in tissues are present when bacterial contamination occurs intraoperatively. Administration of an antimicrobial agent within 1 hour or 2 hours (vancomycin) before surgery has been demonstrated to decrease the risk of wound infection. Accordingly, administration of the prophylactic agent is recommended at least 60 minutes before surgical incision to ensure adequate tissue concentrations at the start of the procedure, although with anti microbial agents requiring longer administration times, such as glycopeptides and amino glycosides, administration is recommended 120 minutes before the surgery begins. Duration of Administration of Antimicrobial Agents A single dose of an antimicrobial agent that provides adequate tissue concentrations throughout the surgical procedure is suffcient. When surgery is prolonged (more than 3 hours), major blood loss occurs, or an antimicrobial agent with a short half-life is used, redosing every 1 to 2 half-lives of the drug should provide adequate antimicrobial con centrations during the procedure. For example, during spinal rod placement, cefazolin may be administered every 3 to 4 hours because of large-volume blood loss. Recommended Antimicrobial Agents An antimicrobial agent is chosen on the basis of bacterial pathogens most likely to cause infectious complications after the specifc procedure, the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of these pathogens, and the safety and effcacy of the drug. New, more broad spectrum and more costly antimicrobial agents generally are not recommended unless prophylactic effcacy has been proven to be superior to drugs of established beneft or there is a shift in organisms causing surgical site infections or in their antimicrobial resistance patterns. Doses and routes of administration are determined on the basis of the need to achieve therapeutic blood and tissue concentrations throughout the procedure. For colorec tal surgery or appendectomy, effective prophylaxis requires antimicrobial agents that are active against aerobic and anaerobic intestinal fora. Physicians should be aware of potential interactions and adverse effects associated with prophylactic antimicrobial agents and other medica tions the patient may be receiving. Routine use of extended spectrum cephalosporins for surgical prophylaxis generally is not recommended. Special considerations should be given to the patient with congenital heart disease who undergoes surgery. The committee has restricted recommendations for prophylaxis to a narrower group of people who have cardiac abnormalities and for fewer procedures than in the past. Although previous recommendations stressed prophylaxis for people undergoing procedures most likely to produce bacteremia, this revision stresses cardiac conditions in which an episode of infective endocarditis would have high risk of adverse outcome. Prophylaxis no longer is recommended solely to prevent endocarditis for procedures involving the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. The cardiac conditions and proce dures for which endocarditis prophylaxis is recommended are shown below, and specifc prophylactic regimens are shown in Table 5. Antibiotic prophylaxis is reason able for these patients who undergo an invasive procedure of the respiratory tract that involves incision of the respiratory tract mucosa. Physicians should consult the published recommendations for further details circ. Cardiac conditions associated with the highest risk of adverse outcome from endo carditis for which prophylaxis with dental procedures is reasonable include the following :2. A Guideline From the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Diseases Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. The following procedures and events do not require prophylaxis: routine anesthetic injections through noninfected tissue, taking dental radiographs, placement of removable prosthodontic or orthodontic appli ances, adjustment of orthodontic appliances, placement of orthodontic brackets, shed ding of deciduous teeth, and bleeding from trauma to the lips or oral mucosa. Prevention of Neonatal Ophthalmia Ophthalmia neonatorum is defned as conjunctivitis occurring within the frst 4 weeks of life. Routine prophylaxis is mandated in most jurisdictions in Canada and the United States. Neonates with ophthalmia neonatorum require clinical evaluation with appropriate laboratory test ing and prompt initiation of therapy. Major and Minor Etiologies in Ophthalmia Neonatorum Etiology of Incubation Ophthalmia Proportion of Period Severity of Neonatorum Cases (Days) Conjunctivitisa Associated Problems Chlamydia 2%?40% 5?14 + Pneumonitis 3 wk?3 mo trachomatis (see Chlamydial Infec tions, p 272) Neisseria Less than 1% 2?7 +++ Disseminated infec gonorrhoeae tion (see Gonococcal Infections, p 336) Other bacterial 30%?50% 5?14 + Variable microbesb Herpes simplex Less than 1% 6?14 + Disseminated infection, virus meningoencephalitis (see Herpes Simplex, p 398); keratitis and ulceration also possible Chemical Varies with 1 +. In addition, a prophylactic agent should be in instilled into the eyes of all newborn infants, including infants born by cesarean delivery. Although infections usually are transmitted during passage through the birth canal; ascending infection can occur. Three agents are licensed for neonatal ocular prophylaxis in the United States: 1% silver nitrate solution, 0. Although all 3 agents are effective against gonococcus, none prevents transmission of C trachomatis from mother to infant. Topical antimicrobial therapy alone is inadequate for N gonorrhoeae-exposed or infected infants and is not necessary when systemic antimicrobial therapy is administered. Frequent eye irrigations with saline solution should be performed until resolution of the discharge. Chlamydial Ophthalmia Neonatal ophthalmia attributable to Chlamydia trachomatis is not as clinically severe as gonococcal conjunctivitis. Chlamydial conjunctivitis in the neonate is characterized by a mucopurulent discharge, eyelid swelling, a propensity to form membranes on the palpe bral conjunctiva, and lack of a follicular response. Treatment is 14 days of oral antimi crobial agent (see Chlamydial Infections, p 272). Topical therapy is unnecessary and does not prevent development of chlamydial pneumonia (see Chlamydial Infections, p 272). Nongonococcal, Nonchlamydial Ophthalmia Neonatal ophthalmia can be caused by many different bacterial pathogens (see Table 5. Silver nitrate, povidone-iodine, and erythromycin are effective for preventing non gonococcal, nonchlamydial conjunctivitis during the frst 2 weeks of life. Administration of Neonatal Ophthalmic Prophylaxis Before administering local prophylaxis, each eyelid should be wiped gently with sterile cotton. Two drops of a 1% silver nitrate solution or a 1-cm ribbon of antimicrobial oint ment (0.

Syndromes

- Abnormal heart rate

- Amino acids - urine

- Nuts and seeds, including almonds, hazelnuts, mixed nuts, peanuts, peanut butter, sunflower seeds, or walnuts (just watch how much you eat, because nuts are high in fat)

- Swelling of tongue

- Electromyogram (EMG)

- Slow urinary stream

- Restlessness

- Gastroscopy

Order generic astelin online

The esophagus begins at the level of the oropharynx; it then enters the superior Fig allergy medicine phenylephrine astelin 10ml sale. Anatomic relationships between the esophagus, airway, mediastinum behind the trachea and left recurrent laryngeal aorta, diaphragm, and stomach. It continues caudad, passing poste rior to the left atrium but anterior to the descending thoracic aorta. At the level of T10, the esophagus joins the stomach Structurally, the esophagus is made up of four layers: the at the cardia after passing through the hiatus in the right mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and adventitia. In the upper third of the esophagus, this the superior and inferior thyroid arteries whereas the mid muscularis propria is skeletal muscle but in the distal third it esophagus receives its blood supply from the bronchial and is smooth muscle, and the mid-section is mixed skeletal and right intercostal arteries as well as branches of the descending smooth muscle. Distally, the esophagus is supplied by branches of the the proximal origin of the esophagus where the inferior pha left gastric, left inferior phrenic and splenic arteries. The azy a 2?4 cm length of asymmetric circular smooth muscle within gous and gastric veins form an anastomotic network between the diaphragmatic hiatus. Esophageal neuroanatomic path nitroprusside, dopamine, beta-adrenergic agonists, tricyclic ways are shared by both the cardiac and respiratory systems, antidepressant medications, and opioids. Anesthesia for Esophageal Surgery 417 Nonmalignant Disorders of the Esophagus comprise approximately 5?15% of hiatal hernias [2]. Relative to laparotomy Gastroesophageal reflux and hiatal hernia may be present inde or transthoracic approaches, laparoscopic surgeries may pro pendently or may coexist. Esophageal strictures may be caused duce considerably less pain, eliminate the need for a tube tho by a number of insults but are frequently related to gastroe racostomy, utilize smaller incisions which decrease the risk sophageal reflux. Gastroesophageal reflux is a common disor of postoperative incisional hernias, and provide visualization der and depending on diet and lifestyle, may affect up to 80% for the diagnosis of other intra-abdominal pathology. The distal esophagus and the esophagogastric ical therapy, esophageal stricture, pulmonary symptoms such junction are mobilized with preservation of the vagus nerve and as asthma and chronic cough, and severe erosive esophagitis. Hiatal her dilator orally and advances it through the gastroesophageal nias include the sliding hiatal hernia (type I) and paraesopha junction. Sliding a 2 cm fundoplication wrap is created with the fundus of the hiatal hernias are most common and occur when the gastroe stomach. The dilator is removed and the fundoplication wrap sophageal junction and part of the fundus of the stomach her placed below the diaphragm without tension. Nissen fundoplication yields a high patient satisfaction reducing barrier pressure between the esophagus and stomach, rate (90?95%) when the procedure is performed by experi which in turn promotes reflux. The transthoracic partial fundoplica stomach, typically the fundus, herniates into the thorax ante tion (Belsey) is similar to the Nissen fundoplication but the rolateral to the distal esophagus (see Figs. Note widening of the muscular hiatal orifice that allows cephalad herniation of the gastric cardia. Esophageal strictures that are not amenable a transthoracic approach, aims to lengthen the esophagus to to dilation may require esophagoplasty or esophagectomy. Through a thoracotomy incision the esophagus can be easily isolated and encircled, the hernia sac opened, its contents reduced to the abdomen, and the hiatus narrowed. Esophageal lengthening and fundoplication procedures are also frequently performed as part of the same procedure. Esophageal Perforation and Rupture Esophageal perforation typically occurs in the hospital and is often iatrogenic. Perforation or disruption of the esophagus may also occur from external trauma, typically gunshot wounds or Fig. Chest radiograph demonstrating a large left-sided type 4 less commonly, from blunt trauma, from a foreign body, or paraesophageal hernia. Surgical procedure Surgical incision(s)/approach Anesthetic considerations Transthoracic total fundoplication (Nissen) Left thoracotomy Pain control Transthoracic partial fundoplication (Belsey) One lung ventilation Collis gastroplasty Aspiration risk Thoracoscopic esophagomyotomy Left thoracoscopy (4?5 ports) Pain control Heller myotomy and modified Heller myotomy Left thoracotomy One lung ventilation High aspiration risk Intraoperative esophagoscopy Transhiatal esophagectomy Midline laparotomy Aspiration risk Left cervical Incision Risk of tracheobronchial injury, bleeding, cardiac compression, and dysrhythmias Transthoracic esophagectomy (Ivor Lewis) Midline laparotomy Aspiration risk Right thoracotomy One lung ventilation Three hole esophagectomy (McKewin) Right thoracotomy Protective ventilation Midline laparotomy Fluid and hemodynamic management to optimize Left cervical incision oxygen delivery Pain control Early extubation Minimally invasive esophagectomy Right thoracoscopy (4 ports) Aspiration risk Laparoscopy (5 ports) Protective ventilation Left cervical incision (variable) Procedure duration 30. This rupture of the distal esophagus occurs under high glion cells in the myenteric plexus. This causes an imbalance pressure which forces gastric contents into the mediastinum between excitatory and inhibitory neurons which results in and pleura [9]. Other primary motor Clinical presentation may be related to the mode of injury disorders of the esophagus include nutcracker esophagus and but is often nonspecific. Secondary achalasia is most often [10], though fever, dyspnea, and crepitus also present not caused by Chagas disease, a systemic disease due to infection uncommonly. Other secondary motor disor taneous esophageal rupture includes chest pain, vomiting, ders are associated with systemic disease processes such as and subcutaneous emphysema. These Achalasia progresses slowly and thus when patients finally patients may present with septic shock and are likely to dete present for treatment they are often at advanced stages of the riorate rapidly, particularly without aggressive resuscitation disease. As the esophagus dilates, regurgita Evaluation for esophageal perforation or rupture includes a tion becomes a more frequent problem. Treatment of esophageal rupture or perforation depends mainly on the extent and location of the tear and the disease state of the esophagus. The time interval between injury and repair may also play a role in determining the appropriate strategy for treatment. Perforation of the cervical esophagus may be treated solely by drainage; surgical repair is preferred for thoracic or abdominal esophageal perforations. In a stable patient without severe esophageal pathology, primary clo sure of a thoracic or abdominal esophageal perforation can be attempted. Conservative nonoperative therapies emphasizing aggressive drainage of fluid collections and appropriate antibiotic therapy are preferred by some clini cians for stable patients with contained esophageal leaks [12] and may be associated with acceptably low morbidity and mortality [12, 13]. Case reports and small case series have also demonstrated the efficacy of treating esophageal perfora tion and esophageal anastomotic leaks with self-expandable plastic and metallic stents [14?16]. This thoracic level barium swallow esophagogram illus Achalasia is a disease of impaired esophageal motility, most trates a classic radiologic feature of achalasia bird-beak appearance often affecting the distal esophagus. The superiority of surgical myotomy with Esophageal diverticula are classified according to their ana fundoplication is supported by a recent systematic review and tomic location (cervical or thoracic) and pathophysiology meta-analysis [22]. Most diverticula are acquired Laparoscopic esophagomyotomy is performed with the and occur in an elderly patient population. Pulsion or pseudodi patient in modified lithotomy, reverse Trendelenberg position verticula are the most common form and consist of a localized and includes an anterior longitudinal myotomy of the distal outpouching which lacks a muscular covering; that is, the wall esophagus, esophagogastric junction, and proximal stomach. Epiphrenic diverticula are ization of the lower esophagus and cardioesophageal junction located within the thoracic esophagus, typically in the distal [23, 24]. True or traction diverticula occur within the are performed via a left thoracotomy incision and differ in the middle one third of the thoracic esophagus as a result of parae extent of the myotomy incision and the inclusion of a fun sophageal granulomatous mediastinal lymphadenitis usually doplication to minimize reflux. The Heller procedure utilizes due to tuberculosis or histoplasmosis and are characterized by a shorter myotomy incision extended only 1 cm or less onto full-thickness involvement of the esophageal wall. The modified Heller myotomy includes a 10 cm ticula are typically small and most are asymptomatic. Patients may also complain of hali to be safe, effective, and durable treatments for achalasia tosis, gurgling associated with swallowing, and symptoms [25?37]. Patient outcomes after minimally invasive myo associated with aspiration such as nighttime cough, hoarse tomy surgery for achalasia generally favor the laparoscopic ness of voice, bronchospasm, and chronic respiratory infec approaches, however. Diagnostic confirmation is accomplished with barium patients experience superior dysphagia relief and less postop contrast study which clearly demonstrates the diverticulum. This difference accomplished via a left cervical incision and includes a cri may result from the limitations in extending the myotomy copharyngeal myotomy. While the myotomy may be sufficient incision into the stomach and creating a fundoplication wrap therapy for small diverticula, larger sacs require diverticulec from the thoracoscopic approach. Placement of an esopha symptoms may include dysphagia, chest pain, regurgitation geal stent may provide suitable palliation [48] and survival of ingested foods, and symptoms of aspiration. While squamous cell carcinoma still accounts for the vast majority of esophageal cancers worldwide, the incidence of adenocarcinoma has risen sharply throughout the Western world, now accounting for nearly half of esophageal cancers in many countries [57, 58]. Potential etiologic and predisposing factors identified through epidemiologic study include tobacco use and excessive alco hol ingestion, gastroesophageal reflux, obesity, achalasia, and low socioeconomic status [57]. Clinical presentation of patients with esophageal cancer is variable; patients may present with symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia, and progressive weight loss. Patient evaluation should include a thorough history and physical examination with attention to local tumor effects, possible sites of metasta sis, and general health. Clinical investigations include the bar ium contrast swallow study to define esophageal anatomy and esophagogastroscopy to permit biopsy and definitive identifi cation of tumor type. A thoracic level barium swallow esophagogram which dem associated with esophagectomy, many centers are employing onstrates a large mid-esophageal diverticulum filled with contrast. The close surveillance of many patients with premalignant disease of the swallow examination (see Fig.

Order astelin online

If a measles-containing vaccine is admin istered before 12 months of age allergy symptoms dark circles under eyes astelin 10 ml otc, the child should receive 2 additional doses of measles containing vaccine at the recommended ages and interval (see Fig 1. An additional factor in selecting an immunization schedule is the need to achieve a uniform and regular response. For example, live-virus rubella vaccine evokes a predictable response at high rates after a single dose. With many inactivated or component vaccines, a primary series of doses is necessary to achieve an optimal initial response in recipients. For example, some people respond only to 1 or 2 types of poliovirus after a single dose of poliovirus vaccine, so multiple doses are given to produce antibody against all 3 types, thereby ensuring complete protection for the person and maximum response rates for the population. For some vaccines, periodic booster doses (eg, with tetanus and diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis antigen) are administered to maintain protection. This information is particularly important for scheduling immunizations for children with lapsed or missed immunizations and for people preparing for international travel (see Simultaneous Administration of Multiple Vaccines, p 33). Data indicate possible impaired immune responses when 2 or more parenterally administered live-virus vaccines are not given simultaneously but within 28 days of each other; therefore, live-virus vaccines not admin istered on the same day should be given at least 28 days (4 weeks) apart whenever possi ble. No minimum interval is required between administration of different inactivated vaccines. The recommended childhood (0 through 6 years of age), adolescent (7 through 18 years of age), and catch-up immunization schedules in Fig 1. These schedules are reviewed regularly, and updated national schedules are issued annually in February; schedules are available at Special attention should be given to footnotes on the sched ule, which summarize major recommendations for routine childhood immunizations. The use of a combination vaccine generally is preferred over separate injec tions of its equivalent component vaccines. Considerations should include provider assess ment, patient preference, and the potential for adverse events. The provider assess ment should include the number of injections, vaccine availability, the likelihood of improved coverage, the likelihood of patient return, and storage and cost considerations. Web-based childhood immunization schedulers using the current vaccine recommendations are available for parents, care givers, and health care profes sionals to make instant immunization schedules for children, adolescents, and adults (see Immunization Schedulers, p 5, or For children in whom early or rapid immunization is urgent or for children not immu nized on schedule, simultaneous immunization with multiple products allows for more rapid protection. In addition, in some circumstances, immunization can be initiated ear lier than at the usually recommended time or schedule, or doses can be given at shorter intervals than are recommended routinely (for guidelines, see the disease-specifc chapters in Section 3). The fnal dose of the hepatitis B vac cine series should be administered at least 16 weeks after the frst dose and no earlier than 24 weeks of age. Infuenza vaccine should be administered before the start of infuenza season but provides beneft if administered at any time during the infuenza season (ie, usually through March) (see Infuenza, Timing of Vaccine Administration, p 450). In many instances, the guide lines will be applicable to children in other countries, but individual pediatricians and recommending committees in each country are responsible for determining the appro priateness of the recommendations for their setting. Always use this table in conjunction with the accompanying childhood and adolescent immunization schedules (Figures 1 and 2) and their respective footnotes. Persons aged 4 months through 6 years Minimum Age Minimum Interval Between Doses Vaccine for Dose 1 Dose 1 to dose 2 Dose 2 to dose 3 Dose 3 to dose 4 Dose 4 to dose 5 Hepatitis B Birth 4 weeks and at least 16 weeks after frst dose; minimum age for8 weeks the fnal dose is 24 weeks Rotavirus1 6 weeks 4 weeks 4 weeks1 Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis2 6 weeks 4 weeks 4 weeks 6 months 6 months2 4 weeks3 if frst dose administered at younger than age 12 months4 weeks if current age is younger than 12 months3 8 weeks (as fnal dose) Haemophilus infuenzae 8 weeks (as fnal dose) if current age is 12 months or older and frst dose8 weeks (as fnal dose) this dose only necessaryfor children aged 12 type b3 6 weeks if frst dose administered at age 12?14 months administered at younger than age 12 months and second months through 59 months No further doses needed dose administered at younger than 15 months before age 12 monthswho received 3 doses if frst dose administered at age 15 months or older if previous dose administered at age 15 months or olderNo further doses needed 4 weeks 4 weeks this dose only necessary8 weeks (as fnal dose) if frst dose administered at younger than age 12 months if current age is younger than 12 months for children aged 12 4 if frst dose administered at age 12 months or older or current8 weeks (as fnal dose for healthy children) 8 weeks (as fnal dose for healthy children) months through 59 months Pneumococcal 6 weeks age 24 through 59 months if current age is 12 months or older before age 12 months orwho received 3 doses No further doses needed for healthy children if previous dose administered atNo further doses needed for children at high risk for healthy children if frst dose administered atage 24 months or older age 24 months or older who received 3 doses at any age 5 6 months5 Inactivated poliovirus 6 weeks 4 weeks 4 weeks minimum age 4 years forfnal dose Meningococcal6 9 months 8 weeks6 Measles, mumps, rubella7 12 months 4 weeks Varicella8 12 months 3 months Hepatitis A 12 months 6 months Persons aged 7 through 18 years Tetanus, diphtheria/ tetanus, if frst dose administered at younger than age 12 months4 weeks if frst dose administered at6 months diphtheria, pertussis9 7 years9 4 weeks 6 months younger than if frst dose administered at 12 months or older age 12 months Human papillomavirus10 9 years Routine dosing intervals are recommended10 Hepatitis A 12 months 6 months Hepatitis B Birth 4 weeks (and at least 16 weeks after frst dose)8 weeks Inactivated poliovirus5 6 weeks 4 weeks 4 weeks5 6 months5 Meningococcal6 9 months 8 weeks6 Measles, mumps, rubella7 12 months 4 weeks if person is younger than age 13 years3 months Varicella8 12 months 4 weeks if person is aged 13 years or older 1. Vaccination should not be years or older and at least 6 months after the previous dose. Suspected cases of vaccine-preventable diseases should be reported to the state or local health department. Modifcations may be made by the ministries of health in individual countries on the basis of local considerations. Recommendations for vaccine schedules in Europe are available at the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control ( Minimum Ages and Minimum Intervals Between Vaccine Doses Immunizations are recommended for members of the youngest age group at risk of experiencing the disease for whom effcacy, immunogenicity, and safety have been dem onstrated. Most vaccines in the childhood and adolescent immunization schedule require 2 or more doses for stimulation of an adequate and persisting antibody response. Studies have demonstrated that the recommended age and interval between doses of the same antigen(s) provide optimal protection. Administering doses of a multidose vaccine at intervals shorter than those in the childhood and adolescent immunization schedules might be necessary in circum stances in which an infant or child is behind schedule and needs to be brought up to date quickly or when international travel is pending. In these cases, an accelerated schedule using minimum age or interval criteria can be used. Vaccines should not be administered at intervals less than the recommended mini mum or at an earlier age than the recommended minimum (eg, accelerated schedules). The frst is for measles vaccine during a measles outbreak, in which case the vaccine may be administered as early as 6 months of age. However, if a measles-containing vaccine is administered before 12 months of age, the dose is not counted toward the 2-dose measles vaccine series, and the child should be reimmunized at 12 through 15 months of age with a measles-containing vaccine. A third dose of a measles-containing vaccine is indicated at 4 through 6 years of age but can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the second dose (see Measles, p 489). The second consideration involves administering a dose a few days earlier than the minimum interval or age, which is unlikely to have a substantially negative effect on the immune response to that dose. Although immunizations should not be scheduled at an interval or age less than the minimums listed in Fig 1. In this situ ation, the clinician can consider administering the vaccine before the minimum interval or age. If the child is known to the clinician, rescheduling the child for immunization closer to the recommended interval is preferred. If the parent or child is not known to the clinician or follow-up cannot be ensured (eg, habitually misses appointments), admin istration of the vaccine at that visit rather than rescheduling the child for a later visit is preferable. Vaccine doses administered 4 days or fewer before the minimum interval or age can be counted as valid. This 4-day recommendation does not apply to rabies vac cine because of the unique schedule for this vaccine. Doses administered 5 days or more before the minimum interval or age should not be counted as valid doses and should be repeated as age appropriate. The repeat dose should be spaced after the invalid dose by at least 4 weeks (Fig 1. However, such vaccines have been considered interchangeable by most experts when administered according to their rec ommended indications, although data documenting the effects of interchangeability are limited. An example of similar vaccines used in different schedules that are not recommended as interchangeable is the 2-dose HepB vac cine option currently available for adolescents 11 through 15 years of age. Infants and children have suffcient immunologic capacity to respond to multiple vaccines. No contraindications to the simultaneous administration of multiple vaccines routinely 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immune response to one vaccine generally does not interfere with responses to other vaccines. Because simultaneous administration of routinely recommended vaccines is not known to affect the effectiveness or safety of any of the recommended childhood vaccines, simul taneous administration of all vaccines that are appropriate for the age and immunization status of the recipient is recommended. When vaccines are administered simultaneously, 1 separate syringes and separate sites should be used, and injections into the same extrem ity should be separated by at least 1 inch so that any local reactions can be differentiated. Simultaneous administration of multiple vaccines can increase immunization rates signif cantly. Some vaccines administered simultaneously may be more reactogenic than others (see disease-specifc chapters). Individual vaccines should never be mixed in the same syringe unless they are specifcally licensed and labeled for administration in one syringe. Combination Vaccines Combination vaccines represent one solution to the issue of increased numbers of injec tions during single clinic visits and generally are preferred over separate injections of equivalent component vaccines. Health care professionals who provide immunizations should stock combination and monovalent vaccines needed to immunize children against all diseases for which vaccines are recommended, but all available types or brand-name products do not need to be stocked. It is recognized that the decision of health care pro fessionals to implement use of new combination vaccines involve complex economic and logistical considerations. Factors that should be considered by the provider, in consulta tion with the parent, include the potential for improved vaccine coverage, the number of injections needed, vaccine safety, vaccine availability, interchangeability, storage and cost issues, and whether the patient is likely to return for follow-up. When patients have received the recommended immunizations for some of the components in a combination vaccine, administering the extra antigen(s) in the combin ation vaccine is permissible if they are not contraindicated and doing so will reduce the number of injections required. Excessive doses of toxoid vaccines (diphtheria and tetanus) may result in extensive local reactions.

Buy cheap astelin 10 ml on-line